REPORT: Reduce Incidents by Understanding Why Climbers Make Mistakes

Facilities have long been trying to answer the vexing question of why climbers make mistakes that can result in injury. Knowing this answer would go a long way in helping climbing gyms’ risk management programs and reduce incident rates.

To help understand why mistakes happen, the CWA recently sponsored a research project to study climber behavior in climbing gyms and what gyms can do to build good awareness and culture around risk.

The CWA partnered with Jon Heshka, a professor who teaches in the Adventure Studies Department and Law School at Thompson Rivers University in British Colombia, Canada.

|

|

Jon Heshka |

Surveys were completed by nearly 700 climbers at eight different climbing gyms in the southwest U.S. and western Canada. Jon visited these gyms, spending three days at each of them, observing climbers’ behaviors and practices to better undertand how these mistakes happen.

Surprisingly, the only prior studies to look at this topic were done in Europe and are rather dated. A German Alpine Club study from 2004 reported that one-third of belayers used their belay device poorly or incorrectly and that nearly half of climbers did not do a belay check or check their partner’s tie-in. The Swiss Alpine Club and the UIAA reported in 2011 that one in three climbers produce errors in belaying or climbing that would cause serious injury in the event of a fall and that there is one ground fall for every 20,000 gym visits. It also reported that “this risk can be reduced ten or one hundred-fold through a risk management program that includes ongoing training regarding best practices.”

Every year, people get hurt in climbing gyms. The cause is almost always climber error, i.e., human factors. Jon’s project studied, among other things, the degree of care that climbers took tying-in, threading their belay devices, clipping into auto-belays, checking one another’s connections into the system and communications while climbing.

While the root cause of incidents is the initial error, climbers and their partners double-checking clip-ins, tie-ins, and belay devices would prevent a large majority of rope climbing incidents in the first place.

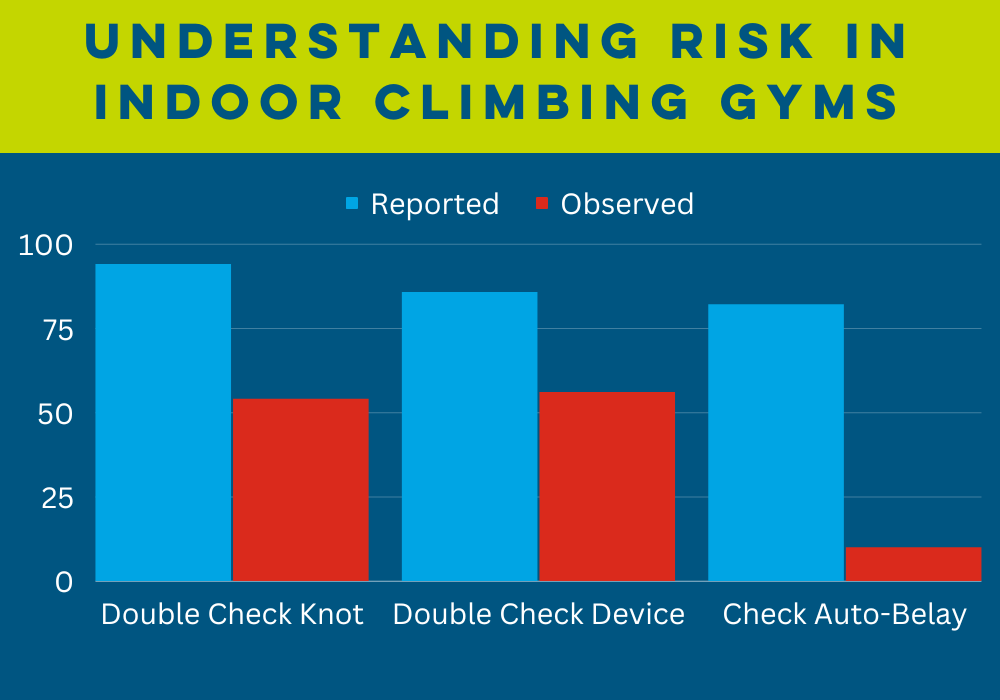

Climbers were asked in the survey a series of questions concerning their climbing practices, which led to some very interesting and insightful data showing that there is a disconnect between how careful climbers think they are versus how careful they actually are (see graphic below).

Complacency is the most cited reason why climbers aren’t properly tying-in, belaying, clipping-in, and partner checking. Jon’s research suggests there are other possible explanations including over-confidence, continuation bias, over-excitement, inattentiveness, distraction, and the absence of a systematized approach to starting a climb.

The Disconnect Between Perception of Safety and Safety

The survey results suggest that climbers beleiver that they are very careful about tying-in, belaying, clipping-in and communicating.

These results, however, are at odds with behavior that was observed at climbing gyms.

- 87.6% of climbers completely agreed and another 7.8% mostly agreed that they double-check to ensure the rope is tied properly.

- 85.7% of climbers completely agreed and another 9.9% mostly agreed that they double-check to ensure the belay device is threaded properly.

- 85.6% of climbers completely agreed and another 8.9% mostly agreed that they double-check to ensure the its carabiner is locked.

- 82.9% of climbers completely agreed and another 10.3% mostly agreed that they double-check to ensure they’re properly clipped and locked into the auto-belay.

- Lastly, 55.8% of climbers completely agreed and another 33.8 % mostly agreed that they communicate precisely with their partner before the climb, during the climb, and while being lowered off the climb.

- Only 54% of climbers double-checked if they were properly tied-in, 56% double-checked their belay device and 10% double-checked their auto-belay.

- 32.5% of climbers verbally communicated that they were ready to lower; another 8.3% either gave a thumbs-up or looked and nodded that they were ready to lower.

- It was not possible to determine what was said or not said at the start of the climb.

Download The Preliminary Report For Research Findings

So what can climbing gyms do?

To a degree, climbing gyms are already reducing their operational risks through waivers, orientations and belay tests with new climbers, staff training, signage, etc.

The use of belay gates on auto-belays has not been fully embraced by climbing gyms, but there are several safety advantages to adding in this additional step for the climber. In addition to obstructing a climber from jumping on a route, what they do is ‘disrupt’ the climber’s thinking, so they have to refocus on the correct saferty process rather than going on auto-pilot.

Reducing distractions by disallowing the use of two earbuds while climbing and prohibiting cell phones on climbing mats are other risk management strategies climbing gyms can embrace.

Climbing gyms need to clarify the extent to which their staff supervise or monitor climbers, and communicate that with them. Supervision can hypothetically range from being modelled after lifeguards at a swimming pool to having staff occasionally walk the floor and look at climbers. Regardless of the model used, it has to be clearly conveyed to climbers.

The climbing community needs to come up with a universal and systematized approach to starting a climb.

It exists with building anchors (variants include ERNEST – Equalized, Redundant, No Extension, Solid/Strong/Secure, Timely, and SERENE-A – Solid/Strong/Secure, Equalized, Redundant, Efficient, No Extension, Angles) and rappelling (ABCDE – Anchor, Buckles, Carabiner, Descender, Edges). Such a uniform approach to starting a climb would make it less haphazard and reduces the likelihood of skipping a step.

Jon will continue with his research and will report his findings to the CWA and elsewhere.

Jon Heshka's preliminary report is available for free to the indoor climbing community.

This article was co-written by Jon and Garnet Moore, the CWA's Director of Standards and Regulatory Affairs. For any questions, please contact Garnet here.